- Théorie des catégories

-

La théorie des catégories étudie les structures mathématiques et les relations qu'elles entretiennent.

Les catégories sont utilisées dans la plupart des branches mathématiques et dans certains secteurs de l'informatique théorique et en mathématiques de la physique. Elles forment une notion unificatrice. Cette théorie a été mise en place par Samuel Eilenberg et Saunders Mac Lane en 1942-1945, en lien avec la topologie algébrique, et propagée dans les années 1960-1970 en France par Alexandre Grothendieck, qui en fit une étude systématique. À la suite des travaux de William Lawvere, la théorie des catégories est utilisée depuis 1969 pour définir la logique et la théorie des ensembles ; elle peut donc, comme cette dernière, être considérée comme fondement des mathématiques.

Sommaire

Éléments de base

Morphismes

L'étude des catégories, très abstraite, fut motivée par l'abondance de caractéristiques communes à diverses classes liées à des structures mathématiques.

Voici un exemple. La classe Grp des groupes comprend tous les objets ayant une « structure de groupe ». Plus précisément, Grp comprend tous les ensembles G munis d'une opération qui satisfait un certain ensemble d'axiomes (associativité, inversibilité, élément neutre). Des théorèmes peuvent ainsi être prouvés en effectuant des déductions logiques à partir de cet ensemble d'axiomes. Par exemple, ils apportent la preuve directe que l'élément identité d'un groupe est unique.

Au lieu d'étudier simplement l'objet seul (les groupes) qui possède une structure donnée, comme les théories mathématiques l'ont toujours fait, la théorie des catégories met l'accent sur les morphismes et les processus qui préservent la structure entre deux objets. Il apparaît qu'en étudiant ces morphismes l'on est capable d'en apprendre plus sur la structure des objets.

Dans notre exemple, les morphismes étudiés sont les homomorphismes de groupes. Un homomorphisme de groupe entre deux groupes préserve la structure de groupe d'une manière très précise ; c'est un processus qui à un groupe en associe un autre, tout en préservant toutes les informations sur la structure du premier groupe au sein du second groupe. Ainsi :

- à chaque élément x du groupe de départ est associé un élément f(x) du groupe d'arrivée ;

- à chaque opération

du groupe de départ est associée une opération

du groupe de départ est associée une opération  du groupe d'arrivée.

du groupe d'arrivée.

Une manière équivalente de décrire cette préservation de structure est de dire que toutes les manières d'aller du couple d'éléments quelconques (x,y) à

mènent au même résultat :

mènent au même résultat :- on peut d'abord aller de (x,y) à

par la loi de composition

par la loi de composition  , puis de

, puis de  à

à  par le morphisme f ;

par le morphisme f ; - ou bien l'on peut aller d'abord de (x,y) à (f(x),f(y)) par le morphisme f, puis de (f(x),f(y)) à

par la loi de composition

par la loi de composition  .

.

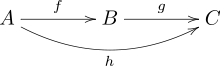

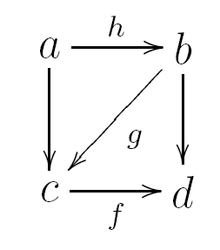

Pour dire que tous ces chemins mènent au même résultat, on peut énoncer que le diagramme qui les représente est commutatif, ou que

.

.L'étude des homomorphismes de groupe fournit un outil pour étudier les propriétés générales des groupes et les conséquences des axiomes relatifs aux groupes.

Il en est de même dans de nombreuses théories mathématiques. Une catégorie est une formulation axiomatique qui relie des structures mathématiques aux fonctions qui les préservent. Une étude systématique des catégories permet de prouver des résultats généraux à partir des axiomes d'une catégorie.

Foncteurs

Une catégorie est elle-même un type de structure mathématique, pour laquelle il existe des processus préservant sa structure. De tels processus sont appelés foncteurs. Un foncteur associe à chaque objet d'une catégorie un objet d'une autre catégorie, et à chaque morphisme d'une catégorie un morphisme dans l'autre catégorie.

On définit ainsi une catégorie des catégories et foncteurs : les objets sont des catégories, et les morphismes sont des foncteurs.

L'étude des catégories et des foncteurs n'est pas seulement celle d'une classe de structures mathématiques et des morphismes qui les relient : elle porte également sur les relations entre diverses classes de structures mathématiques. Cette idée fondamentale apparut d'abord en topologie algébrique : certains problèmes topologiques complexes peuvent être traduits en questions algébriques, qui sont souvent plus faciles à résoudre. Certaines constructions basiques, telles que le groupe fondamental ou le groupoïde fondamental d'un espace topologique, peuvent ainsi être exprimées comme des foncteurs fondamentaux vers la catégorie des groupoïdes, ce qui permet de généraliser le concept dans l'algèbre et dans ses applications.

Transformations naturelles

Par un nouvel effort d'abstraction, les constructions sont souvent « reliées naturellement ». C'est pourquoi l'on définit le concept de transformation naturelle, qui est une manière d'envoyer un foncteur sur un foncteur. Si le foncteur est un morphisme de morphismes, la transformation naturelle est un morphisme de morphismes de morphismes. On peut ainsi étudier de nombreuses constructions mathématiques. La « naturalité », comme le principe de relativité en physique, est un principe plus profond qu'il n'en a l'air au premier regard. Saunders MacLane, coinventeur de la théorie des catégories, a ainsi déclaré : « je n'ai pas inventé les catégories pour étudier les foncteurs ; je les ai inventées pour étudier les transformations naturelles ».

Par exemple, il existe un isomorphisme entre un espace vectoriel de dimension finie et son espace dual, mais cet isomorphisme n'est pas « naturel », dans le sens où sa définition requiert d'avoir choisi une base, dont elle dépend étroitement. En revanche, il existe un isomorphisme naturel entre un espace vectoriel de dimension finie et son espace bidual (le dual de son dual), c'est-à-dire en l'occurrence indépendant de la base choisie. Cet exemple est, historiquement, le premier formulé dans l'article fondateur de Samuel Eilenberg et Saunders MacLane en 1945.

Autre exemple : il existe plusieurs manières de relier les espaces topologiques à la théorie des groupes : homologie, cohomologie, homotopie... L'étude des transformations naturelles permet d'examiner comment ces connexions sont elles-mêmes reliées l'une à l'autre.

Définition

Une catégorie

, dans le langage de la théorie des classes, est la donnée de quatre éléments :

, dans le langage de la théorie des classes, est la donnée de quatre éléments :- d'une classe dont les éléments sont appelés objets,

- d'un ensemble

, pour chaque paire d'objets

, pour chaque paire d'objets  et

et  , dont les éléments

, dont les éléments  sont appelés morphismes (ou flèches) entre

sont appelés morphismes (ou flèches) entre  et

et  , et sont parfois notés

, et sont parfois notés  ,

, - d'un morphisme

, pour chaque objet

, pour chaque objet  , appelé identité sur

, appelé identité sur  ,

, - d'un morphisme

pour toute paire de morphismes

pour toute paire de morphismes  et

et  , appelé composée de

, appelé composée de  et

et  , tel que :

, tel que :

-

- la composition est associative : pour tous morphismes

,

,  et

et  ,

,

,

,

- les identités sont des éléments neutres de la composition : pour tout morphisme

,

,

.

.

- la composition est associative : pour tous morphismes

On demande aussi que :

si

si  .

.Lorsqu'une catégorie est courante, certains lui donnent comme nom l'abréviation du nom de ses objets, entre parenthèses, pour signaler qu'il s'agit de leur catégorie ; nous suivrons ici cette convention.

Une sous-catégorie de

est une catégorie dont les objets sont des objets

est une catégorie dont les objets sont des objets  et dont les flèches sont des flèches (mais pas nécessairement toutes les flèches) de

et dont les flèches sont des flèches (mais pas nécessairement toutes les flèches) de  entre deux objets de la sous-catégorie.

entre deux objets de la sous-catégorie.Exemples

- La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les ensembles, et les flèches les applications, avec la composition usuelle des applications. En particulier, on voit que les objets d'une catégorie ne forment pas forcément un ensemble !

, dont les objets sont les ensembles, et les flèches les applications, avec la composition usuelle des applications. En particulier, on voit que les objets d'une catégorie ne forment pas forcément un ensemble ! - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les espaces topologiques, et les flèches les applications continues, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les espaces topologiques, et les flèches les applications continues, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les espaces métriques, et les flèches les applications uniformément continues, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les espaces métriques, et les flèches les applications uniformément continues, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les monoïdes et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les monoïdes et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les groupes et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les groupes et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les groupes abéliens et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les groupes abéliens et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les anneaux commutatifs unitaires et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle.

, dont les objets sont les anneaux commutatifs unitaires et les flèches les morphismes, avec la composition usuelle. - La catégorie

, dont les objets sont les ensembles ordonnés et les flèches les applications croissantes.

, dont les objets sont les ensembles ordonnés et les flèches les applications croissantes.

Les exemples précédents ont une propriété en commun : les objets sont des ensembles munis d'une structure supplémentaire, et les flèches sont toujours des applications entre les ensembles sous-jacents. Ce sont des foncteur fidèle vers la catégorie des ensembles (dans les cas présents, il s'agit du foncteur oubli, qui fait abstraction des structures considérées pour ne retenir que leur ensemble de base ; par exemple, appliquer le foncteur d'oubli au groupe

donne l'ensemble

donne l'ensemble  ). Toute petite catégorie (i. e. dont les objets forment un ensemble) est concrète, comme les deux suivantes :

). Toute petite catégorie (i. e. dont les objets forment un ensemble) est concrète, comme les deux suivantes :- On se donne un monoïde

, et on définit la catégorie

, et on définit la catégorie  ainsi :

ainsi :

-

- objets : un seul

- flèches : les éléments du monoïde, elles partent toute de l'unique objet pour y revenir ;

- composition : donnée par la loi du monoïde (l'identité est donc la flèche associée à

).

).

- On se donne un ensemble

muni d'une relation réflexive et transitive

muni d'une relation réflexive et transitive  , et on définit la catégorie associée ainsi :

, et on définit la catégorie associée ainsi :

-

- objets : les éléments de l'ensemble ;

- flèches : pour tous objets

et

et  , il existe une flèche de

, il existe une flèche de  vers

vers  si et seulement si

si et seulement si  (et pas de flèche sinon) ;

(et pas de flèche sinon) ; - composition : la composée de deux flèches est la seule flèche qui réunit les deux extrémités (la relation est transitive) ; l'identité est la seule flèche qui relie un objet à lui-même (la relation est réflexive).

- Cet exemple est particulièrement intéressant dans le cas suivant : l'ensemble est l'ensemble des ouverts d'un espace topologique, et la relation est l'inclusion ; cela permet de définir les notions de préfaisceau et de faisceau, via les foncteurs.

- Un exemple de catégorie non concrète : la catégorie homotopique (en) hTop, dont les objets sont les espaces topologiques et dont les morphismes sont les classes d'homotopie d'applications continues.

Catégorie duale

À partir d'une catégorie

, on peut définir une autre catégorie

, on peut définir une autre catégorie  (ou

(ou  ), dite opposée ou duale, en prenant les mêmes objets, mais en inversant le sens des flèches.

), dite opposée ou duale, en prenant les mêmes objets, mais en inversant le sens des flèches.Plus précisément :

, et la composition de deux flèches opposées est l'opposée de leur composition :

, et la composition de deux flèches opposées est l'opposée de leur composition :Il est clair que la catégorie duale de la catégorie duale est la catégorie de départ :

.

.Cette dualisation extrêmement simple permet de symétriser la plupart des énoncés, ce qui peut être douloureux pour les débutants...

Propriétés des flèches

Définitions

Une flèche

est dite un monomorphisme lorsqu'elle vérifie la propriété suivante : pour tout couple

est dite un monomorphisme lorsqu'elle vérifie la propriété suivante : pour tout couple  de flèches

de flèches  (et donc aussi pour tout

(et donc aussi pour tout  ), si

), si  , alors

, alors  .

.Une flèche

est dite un épimorphisme lorsqu'elle vérifie la propriété suivante : pour tout couple

est dite un épimorphisme lorsqu'elle vérifie la propriété suivante : pour tout couple  de flèches

de flèches  (et donc aussi pour tout

(et donc aussi pour tout  ), si

), si  , alors

, alors  .

.Les notions de monomorphisme et d'épimorphisme sont duales l'une de l'autre : une flèche est un monomorphisme si et seulement si elle est un épimorphisme dans la catégorie duale.

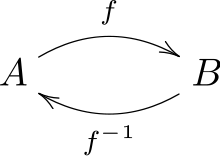

Une flèche est dite un isomorphisme s'il existe une flèche

est dite un isomorphisme s'il existe une flèche  telle que

telle que  et

et  . Cette notion est autoduale.

. Cette notion est autoduale.Exemples

- Dans la catégorie des ensembles, les monomorphismes sont les injections, les épimorphismes sont les surjections et les isomorphismes sont les bijections.

- Un contre-exemple important en théorie des catégories : un morphisme peut à la fois être un monomorphisme et un épimorphisme, sans être pour autant un isomorphisme ; pour voir ce contre-exemple, il faut se placer dans la catégorie des anneaux commutatifs unitaires, et considérer la flèche (unique !)

: elle est un monomorphisme car provient d'une application injective, un épimorphisme par localisation, mais n'est clairement pas un isomorphisme!

: elle est un monomorphisme car provient d'une application injective, un épimorphisme par localisation, mais n'est clairement pas un isomorphisme! - On trouve aussi de tels épimorphisme-monomorphisme non-isomorphiques dans la catégories des espaces topologiques : toute injection y est un monomorphisme, toute surjection est un épimorphisme, les isomorphismes sont les homéomorphismes, mais il y a des fonctions continues à la fois injectives et surjectives qui ne sont pas des homéomorphismes : par exemple l'identité sur un ensemble muni de deux topologies différentes, l'une plus grossière que l'autre.

- Dans la catégorie des ensembles ordonnés les isomorphismes sont les bijections croissantes (elles sont nécessairement strictement croissantes).

Somme et produit d'une famille d'objets en théorie des catégories

Étant donnée une famille

, la somme de la famille

, la somme de la famille  est la donnée d'un objet

est la donnée d'un objet  de

de  et pour tout i d'une flèche

et pour tout i d'une flèche  vérifiant la propriété universelle :

vérifiant la propriété universelle : somme

somme

- quels que soient l'objet

et les flèches

et les flèches  de

de  il existe une unique flèche

il existe une unique flèche  telle que pour tout i le diagramme :

telle que pour tout i le diagramme :

soit commutatif. C'est-à-dire que

.

.Étant donnée une famille

, le produit de la famille

, le produit de la famille  est la donnée d'un objet

est la donnée d'un objet  de

de  et pour tout i d'une flèche

et pour tout i d'une flèche  vérifiant la propriété universelle :

vérifiant la propriété universelle : produit

produit

- quels que soient l'objet

et les flèches

et les flèches  de

de  il existe une unique flèche

il existe une unique flèche  telle que pour tout i le diagramme :

telle que pour tout i le diagramme :

soit commutatif. C'est-à-dire que

.

.

S'ils existent, les sommes et les produits sont uniques aux isomorphismes près[1].On permute ces définitions en inversant les flèches des diagrammes : une somme (respectivement un produit) dans

est un produit (respectivement une somme) dans sa duale.

est un produit (respectivement une somme) dans sa duale.Remarques

- Il arrive parfois que l'on oublie les objets d'une catégorie et que l'on ne s'intéresse plus qu'aux flèches, en substituant la flèche identité à l'objet.

- Il existe la catégorie des petites catégories, où la classe des objets est un ensemble, ainsi que la catégorie des foncteurs d'une petite catégorie à une autre : les morphismes sont les transformations naturelles. On voit ici le rôle joué par la théorie des classes NBG.

- Une catégorie cartésienne est une catégorie munie d'un objet terminal et du produit binaire. Une catégorie cartésienne fermée est une catégorie cartésienne munie de l'exponentiation.

Notes et références

- M. Zisman, Topologie algébrique élémentaire, Armand Colin, 1972, p. 10.

Voir aussi

Bibliographie

Ouvrage de base : (en) Saunders Mac Lane, Categories for the Working Mathematician (en) [détail des éditions]

Ouvrages spécialisés et monographiesEn français :

- Boileau, A. & Joyal, A., 1981, “La logique des topos”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 46 (1): 6–16.

- Dieudonné, J. & Grothendieck, A., 1960 [1971], Éléments de Géométrie Algébrique, Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Grothendieck, A., 1957, “Sur Quelques Points d'algèbre homologique”, Tohoku Mathematics Journal, 9: 119–221.

- Grothendieck, A. et al., Séminaire de Géométrie Algébrique, Vol. 1–7, Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

En anglais :

- Adamek, J. et al., 1990, Abstract and Concrete Categories: The Joy of Cats, New York: Wiley.

- Adamek, J. et al., 1994, Locally Presentable and Accessible Categories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Arzi-Gonczaworski, Z., 1999, “Perceive This as That — Analogies, Artificial Perception, and Category Theory”, Annals of Mathematics and Artificial Intelligence, 26 (1): 215–252.

- Awodey, S., 1996, “Structure in Mathematics and Logic: A Categorical Perspective”, Philosophia Mathematica, 3: 209–237.

- Awodey, S., 2004, “An Answer to Hellman's Question: Does Category Theory Provide a Framework for Mathematical Structuralism”, Philosophia Mathematica, 12: 54–64.

- Awodey, S., 2006, Category Theory, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Awodey, S., 2007, “Relating First-Order Set Theories and Elementary Toposes”, The Bulletin of Symbolic, 13 (3): 340–358.

- Awodey, S., 2008, “A Brief Introduction to Algebraic Set Theory”, The Bulletin of Symbolic, 14 (3): 281–298.

- Awodey, S. & Butz, C., 2000, “Topological Completeness for Higher Order Logic”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 65 (3): 1168–1182.

- Awodey, S. & Reck, E. R., 2002, “Completeness and Categoricity I. Nineteen-Century Axiomatics to Twentieth-Century Metalogic”, History and Philosophy of Logic, 23 (1): 1–30.

- Awodey, S. & Reck, E. R., 2002, “Completeness and Categoricity II. Twentieth-Century Metalogic to Twenty-first-Century Semantics”, History and Philosophy of Logic, 23 (2): 77–94.

- Awodey, S. & Warren, M., 2009, “Homotopy theoretic Models of Identity Types”, Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 146 (1): 45–55.

- Baez, J., 1997, “An Introduction to n-Categories”, Category Theory and Computer Science, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Volume 1290), Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1–33.

- Baez, J. & Dolan, J., 1998a, “Higher-Dimensional Algebra III. n-Categories and the Algebra of Opetopes”, Advances in Mathematics, 135: 145–206.

- Baez, J. & Dolan, J., 1998b, “Categorification”, Higher Category Theory (Contemporary Mathematics, Volume 230), Ezra Getzler and Mikhail Kapranov (eds.), Providence: AMS, 1–36.

- Baez, J. & Dolan, J., 2001, “From Finite Sets to Feynman Diagrams”, Mathematics Unlimited – 2001 and Beyond, Berlin: Springer, 29–50.

- Baianu, I. C., 1987, “Computer Models and Automata Theory in Biology and Medecine”, in Witten, Matthew, Eds. Mathematical Modelling, Vol. 7, 1986, chapter 11, Pergamon Press, Ltd., 1513–1577.

- Barr, M. & Wells, C., 1985, Toposes, Triples and Theories, New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Barr, M. & Wells, C., 1999, Category Theory for Computing Science, Montreal: CRM.

- Batanin, M., 1998, “Monoidal Globular Categories as a Natural Environment for the Theory of Weak n-Categories”, Advances in Mathematics, 136: 39–103.

- Bell, J. L., 1981, “Category Theory and the Foundations of Mathematics”, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 32: 349–358.

- Bell, J. L., 1982, “Categories, Toposes and Sets”, Synthese, 51 (3): 293–337.

- Bell, J. L., 1986, “From Absolute to Local Mathematics”, Synthese, 69 (3): 409–426.

- Bell, J. L., 1988, “Infinitesimals”, Synthese, 75 (3): 285–315.

- Bell, J. L., 1988, Toposes and Local Set Theories: An Introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, J. L., 1995, “Infinitesimals and the Continuum”, Mathematical Intelligencer, 17 (2): 55–57.

- Bell, J. L., 1998, A Primer of Infinitesimal Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bell, J. L., 2001, “The Continuum in Smooth Infinitesimal Analysis”, Reuniting the Antipodes — Constructive and Nonstandard Views on the Continuum (Synthese Library, Volume 306), Dordrecht: Kluwer, 19–24.

- Birkoff, G. & Mac Lane, S., 1999, Algebra, 3rd ed., Providence: AMS.

- Blass, A., 1984, “The Interaction Between Category Theory and Set Theory”, in Mathematical Applications of Category Theory (Volume 30), Providence: AMS, 5–29.

- Blass, A. & Scedrov, A., 1983, “Classifying Topoi and Finite Forcing”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 28: 111–140.

- Blass, A. & Scedrov, A., 1989, Freyd's Model for the Independence of the Axiom of Choice, Providence: AMS.

- Blass, A. & Scedrov, A., 1992, “Complete Topoi Representing Models of Set Theory”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic , 57 (1): 1–26.

- Blute, R. & Scott, P., 2004, “Category Theory for Linear Logicians”, in Linear Logic in Computer Science, T. Ehrhard, P. Ruet, J-Y. Girard, P. Scott, eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–52.

- Borceux, F., 1994, Handbook of Categorical Algebra, 3 volumes, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bunge, M., 1974, “Topos Theory and Souslin's Hypothesis”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 4: 159–187.

- Bunge, M., 1984, “Toposes in Logic and Logic in Toposes”, Topoi, 3 (1): 13–22.

- Carter, J., 2008, “Categories for the working mathematician: making the impossible possible”, Synthese, 162 (1): 1–13.

- Cheng, E. & Lauda, A., 2004, Higher-Dimensional Categories: an illustrated guide book, available at: http://cheng.staff.shef.ac.uk/guidebook/index.html

- Cockett, J. R. B. & Seely, R. A. G., 2001, “Finite Sum-product Logic”, Theory and Applications of Categories (electronic), 8: 63–99.

- Couture, J. & Lambek, J., 1991, “Philosophical Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics”, Erkenntnis, 34 (2): 187–209.

- Couture, J. & Lambek, J., 1992, “Erratum:”Philosophical Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics“”, Erkenntnis, 36 (1): 134.

- Crole, R. L., 1994, Categories for Types, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ehresmann, A. & Vanbremeersch, J.-P., 2007, Memory Evolutive Systems: Hierarchy, Emergence, Cognition, Amsterdam: Elsevier

- Ehresmann, A. C. & Vanbremeersch, J-P., 1987, “Hierarchical Evolutive Systems: a Mathematical Model for Complex Systems”, * Bulletin of Mathematical Biology, 49 (1): 13–50.

- Eilenberg, S. & Cartan, H., 1956, Homological Algebra, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Eilenberg, S. & Mac Lane, S., 1942, “Group Extensions and Homology”, Annals of Mathematics, 43: 757–831.

- Eilenberg, S. & Mac Lane, S., 1945, “General Theory of Natural Equivalences”, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 58: 231–294.

- Eilenberg, S. & Steenrod, N., 1952, Foundations of Algebraic Topology, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ellerman, D., 1988, “Category Theory and Concrete Universals”, Erkenntnis, 28: 409–429.

- Feferman, S., 1977, “Categorical Foundations and Foundations of Category Theory”, Logic, Foundations of Mathematics and Computability, R. Butts (ed.), Reidel, 149–169.

- Feferman, S., 2004, “Typical Ambiguity: trying to have your cake and eat it too”, One Hundred Years of Russell's Paradox, G. Link (ed.), Berlin: De Gruyter, 135–151.

- Freyd, P., 1964, Abelian Categories. An Introduction to the Theory of Functors, New York: Harper & Row.

- Freyd, P., 1965, “The Theories of Functors and Models”. Theories of Models, Amsterdam: North Holland, 107–120.

- Freyd, P., 1972, “Aspects of Topoi”, Bulletin of the Australian Mathematical Society, 7: 1–76.

- Freyd, P., 1980, “The Axiom of Choice”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 19: 103–125.

- Freyd, P., 1987, “Choice and Well-Ordering”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 35 (2): 149–166.

- Freyd, P., 1990, Categories, Allegories, Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Freyd, P., 2002, “Cartesian Logic”, Theoretical Computer Science, 278 (1–2): 3–21.

- Freyd, P., Friedman, H. & Scedrov, A., 1987, “Lindembaum Algebras of Intuitionistic Theories and Free Categories”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 35 (2): 167–172.

- Galli, A. & Reyes, G. & Sagastume, M., 2000, “Completeness Theorems via the Double Dual Functor”, Studia Logical, 64 (1): 61–81.

- Ghilardi, S., 1989, “Presheaf Semantics and Independence Results for some Non-classical first-order logics”, Archive for Mathematical Logic, 29 (2): 125–136.

- Ghilardi, S. & Zawadowski, M., 2002, Sheaves, Games & Model Completions: A Categorical Approach to Nonclassical Porpositional Logics, Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Goldblatt, R., 1979, Topoi: The Categorical Analysis of Logic, Studies in logic and the foundations of mathematics, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Hatcher, W. S., 1982, The Logical Foundations of Mathematics, Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Healy, M. J., 2000, “Category Theory Applied to Neural Modeling and Graphical Representations”, Proceedings of the IEEE-INNS-ENNS International Joint Conference on Neural Networks: IJCNN200, Como, vol. 3, M. Gori, S-I. Amari, C. L. Giles, V. Piuri, eds., IEEE Computer Science Press, 35–40.

- Healy, M. J., & Caudell, T. P., 2006, “Ontologies and Worlds in Category Theory: Implications for Neural Systems”,Axiomathes, 16 (1–2): 165–214.

- Hellman, G., 2003, “Does Category Theory Provide a Framework for Mathematical Structuralism?”, Philosophia Mathematica, 11 (2): 129–157.

- Hellman, G., 2006, “Mathematical Pluralism: the case of smooth infinitesimal analysis”, Journal of Philosophical Logic, 35 (6): 621–651.

- Hermida, C. & Makkai, M. & Power, J., 2000, “On Weak Higher-dimensional Categories I”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 154 (1–3): 221–246.

- Hermida, C. & Makkai, M. & Power, J., 2001, “On Weak Higher-dimensional Categories 2”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 157 (2–3): 247–277.

- Hermida, C. & Makkai, M. & Power, J., 2002, “On Weak Higher-dimensional Categories 3”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 166 (1–2): 83–104.

- Hyland, J. M. E. & Robinson, E. P. & Rosolini, G., 1990, “The Discrete Objects in the Effective Topos”, Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (3), 60 (1): 1–36.

- Hyland, J. M. E., 1982, “The Effective Topos”, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics (Volume 110), Amsterdam: North Holland, 165–216.

- Hyland, J. M. E., 1988, “A Small Complete Category”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 40 (2): 135–165.

- Hyland, J. M. E., 1991, “First Steps in Synthetic Domain Theory”, Category Theory (Como 1990) (Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Volume 1488), Berlin: Springer, 131–156.

- Hyland, J. M. E., 2002, “Proof Theory in the Abstract”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 114 (1–3): 43–78.

- Jacobs, B., 1999, Categorical Logic and Type Theory, Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1977, Topos Theory, New York: Academic Press.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1979a, “Conditions Related to De Morgan's Law”, Applications of Sheaves (Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Volume 753), Berlin: Springer, 479–491.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1979b, “Another Condition Equivalent to De Morgan's Law”, Communications in Algebra, 7 (12): 1309–1312.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1981, “Tychonoff's Theorem without the Axiom of Choice”, Fundamenta Mathematicae, 113 (1): 21–35.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1982, Stone Spaces, Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- Johnstone, P. T., 1985, “How General is a Generalized Space?”, Aspects of Topology, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 77–111.

- Johnstone, P. T., 2001, “Elements of the History of Locale Theory”, Handbook of the History of General Topology, Vol. 3, * Dordrecht: Kluwer, 835–851.

- Johnstone, P. T., 2002a, Sketches of an Elephant: a Topos Theory Compendium. Vol. 1 (Oxford Logic Guides, Volume 43), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Joyal, A. & Moerdijk, I., 1995, Algebraic Set Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kan, D. M., 1958, “Adjoint Functors”, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 87: 294–329.

- Kock, A., 2006, Synthetic Differential Geometry (London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, Volume 51), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed.

- Krömer, R., 2007, Tool and Objects: A History and Philosophy of Category Theory, Basel: Birkhäuser.

- La Palme Reyes, M., John Macnamara, Gonzalo E. Reyes, and Houman Zolfaghari, 1994, “The non-Boolean Logic of Natural Language Negation”, Philosophia Mathematica, 2 (1): 45–68.

- La Palme Reyes, M., John Macnamara, Gonzalo E. Reyes, and Houman Zolfaghari, 1999, “Count Nouns, Mass Nouns, and their Transformations: a Unified Category-theoretic Semantics”, Language, Logic and Concepts, Cambridge: MIT Press, 427–452.

- Lambek, J., 1968, “Deductive Systems and Categories I. Syntactic Calculus and Residuated Categories”, Mathematical Systems Theory, 2: 287–318.

- Lambek, J., 1969, “Deductive Systems and Categories II. Standard Constructions and Closed Categories”, Category Theory, Homology Theory and their Applications I, Berlin: Springer, 76–122.

- Lambek, J., 1972, “Deductive Systems and Categories III. Cartesian Closed Categories, Intuition≠istic Propositional Calculus, and Combinatory Logic”, Toposes, Algebraic Geometry and Logic (Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Volume 274), Berlin: Springer, 57–82.

- Lambek, J., 1982, “The Influence of Heraclitus on Modern Mathematics”, Scientific Philosophy Today, J. Agassi and R.S. Cohen, eds., Dordrecht, Reidel, 111–122.

- Lambek, J., 1986, “Cartesian Closed Categories and Typed lambda calculi”, Combinators and Functional Programming Languages (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Volume 242), Berlin: Springer, 136–175.

- Lambek, J., 1989a, “On Some Connections Between Logic and Category Theory”, Studia Logica, 48 (3): 269–278.

- Lambek, J., 1989b, “On the Sheaf of Possible Worlds”, Categorical Topology and its relation to Analysis, Algebra and Combinatorics, Teaneck: World Scientific Publishing, 36–53.

- Lambek, J., 1993, “Logic without Structural Rules”, Substructural Logics (Studies in Logic and Computation, Volume 2), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 179–206.

- Lambek, J., 1994a, “Some Aspects of Categorical Logic”, Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science IX (Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, Volume 134), Amsterdam: North Holland, 69–89.

- Lambek, J., 1994b, “Are the Traditional Philosophies of Mathematics Really Incompatible?”, Mathematical Intelligencer, 16 (1): 56–62.

- Lambek, J., 1994c, “What is a Deductive System?”, What is a Logical System? (Studies in Logic and Computation, Volume 4), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 141–159.

- Lambek, J., 2004, “What is the world of Mathematics? Provinces of Logic Determined”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 126: 1–3, 149–158.

- Lambek, J. & Scott, P.J., 1981, “Intuitionistic Type Theory and Foundations”, Journal of Philosophical Logic, 10 (1): 101–115.

- Lambek, J. & Scott, P.J., 1983, “New Proofs of Some Intuitionistic Principles”, Zeitschrift für Mathematische Logik und Grundlagen der Mathematik, 29 (6): 493–504.

- Lambek, J. & Scott, P.J., 1986, Introduction to Higher Order Categorical Logic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Landry, E., 1999, “Category Theory: the Language of Mathematics”, Philosophy of Science, 66 (3) (Supplement): S14–S27.

- Landry, E., 2001, “Logicism, Structuralism and Objectivity”, Topoi, 20 (1): 79–95.

- Landry, E., 2007, “Shared Structure need not be Shared Set-structure”, Synthese, 158 (1): 1–17.

- Landry, E. & Marquis, J.-P., 2005, “Categories in Context: Historical, Foundational and philosophical”, Philosophia Mathematica, 13: 1–43.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1963, “Functorial Semantics of Algebraic Theories”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., 50: 869–872.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1964, “An Elementary Theory of the Category of Sets”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A., 52: 1506–1511.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1965, “Algebraic Theories, Algebraic Categories, and Algebraic Functors”, Theory of Models, Amsterdam: North Holland, 413–418.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1966, “The Category of Categories as a Foundation for Mathematics”, Proceedings of the Conference on Categorical Algebra, La Jolla, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1–21.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1969a, “Diagonal Arguments and Cartesian Closed Categories”, Category Theory, Homology Theory, and their Applications II, Berlin: Springer, 134–145.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1969b, “Adjointness in Foundations”, Dialectica, 23: 281–295.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1970, “Equality in Hyper doctrines and Comprehension Schema as an Adjoint Functor”, Applications of Categorical Algebra, Providence: AMS, 1–14.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1971, “Quantifiers and Sheaves”, Actes du Congrès International des Mathématiciens, Tome 1, Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 329–334.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1972, “Introduction”, Toposes, Algebraic Geometry and Logic, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 274, Springer-Verlag, 1–12.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1975, “Continuously Variable Sets: Algebraic Geometry = Geometric Logic”, Proceedings of the Logic Colloquium Bristol 1973, Amsterdam: North Holland, 135–153.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1976, “Variable Quantities and Variable Structures in Topoi”, Algebra, Topology, and Category Theory, New York: Academic Press, 101–131.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1992, “Categories of Space and of Quantity”, The Space of Mathematics, Foundations of Communication and Cognition, Berlin: De Gruyter, 14–30.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1994a, “Cohesive Toposes and Cantor's lauter Ensein ”, Philosophia Mathematica, 2 (1): 5–15.

- Lawvere, F. W., 1994b, “Tools for the Advancement of Objective Logic: Closed Categories and Toposes”, The Logical Foundations of Cognition (Vancouver Studies in Cognitive Science, Volume 4), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 43–56.

- Lawvere, F. W., 2000, “Comments on the Development of Topos Theory”, Development of Mathematics 1950–2000, Basel: Birkhäuser, 715–734.

- Lawvere, F. W., 2002, “Categorical Algebra for Continuum Micro Physics”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 175 (1–3): 267–287.

- Lawvere, F. W., 2003, “Foundations and Applications: Axiomatization and Education. New Programs and Open Problems in the Foundation of Mathematics”, Bulletin of Symbolic Logic, 9 (2): 213–224.

- Lawvere, F. W. & Rosebrugh, R., 2003, Sets for Mathematics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lawvere, F. W. & Schanuel, S., 1997, Conceptual Mathematics: A First Introduction to Categories, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leinster, T., 2002, “A Survey of Definitions of n-categories”, Theory and Applications of Categories, (electronic), 10: 1–70.

- Lurie, J., 2009, Higher Topos Theory, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mac Lane, S., 1950, “Dualities for Groups”, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 56: 485–516.

- Mac Lane, S., 1969, “Foundations for Categories and Sets”, Category Theory, Homology Theory and their Applications II, Berlin: Springer, 146–164.

- Mac Lane, S., 1969, “One Universe as a Foundation for Category Theory”, Reports of the Midwest Category Seminar III, Berlin: Springer, 192–200.

- Mac Lane, S., 1971, “Categorical algebra and Set-Theoretic Foundations”, Axiomatic Set Theory, Providence: AMS, 231–240.

- Mac Lane, S., 1975, “Sets, Topoi, and Internal Logic in Categories”, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics (Volumes 80), Amsterdam: North Holland, 119–134.

- Mac Lane, S., 1981, “Mathematical Models: a Sketch for the Philosophy of Mathematics”, American Mathematical Monthly, 88 (7): 462–472.

- Mac Lane, S., 1986, Mathematics, Form and Function, New York: Springer.

- Mac Lane, S., 1988, “Concepts and Categories in Perspective”, A Century of Mathematics in America, Part I, Providence: AMS, 323–365.

- Mac Lane, S., 1989, “The Development of Mathematical Ideas by Collision: the Case of Categories and Topos Theory”, Categorical Topology and its Relation to Analysis, Algebra and Combinatorics, Teaneck: World Scientific, 1–9.

- Mac Lane, S., 1996, “Structure in Mathematics. Mathematical Structuralism”, Philosophia Mathematica, 4 (2): 174–183.

- Mac Lane, S., 1997, “Categorical Foundations of the Protean Character of Mathematics”, Philosophy of Mathematics Today, Dordrecht: Kluwer, 117–122.

- Mac Lane, S., 1998, Categories for the Working Mathematician, 2nd edition, New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Mac Lane, S. & Moerdijk, I., 1992, Sheaves in Geometry and Logic, New York: Springer-Verlag.

- MacNamara, J. & Reyes, G., (eds.), 1994, The Logical Foundation of Cognition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Makkai, M., 1987, “Stone Duality for First-Order Logic”, Advances in Mathematics, 65 (2): 97–170.

- Makkai, M., 1988, “Strong Conceptual Completeness for First Order Logic”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 40: 167–215.

- Makkai, M., 1997a, “Generalized Sketches as a Framework for Completeness Theorems I”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 115 (1): 49–79.

- Makkai, M., 1997b, “Generalized Sketches as a Framework for Completeness Theorems II”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 115 (2): 179–212.

- Makkai, M., 1997c, “Generalized Sketches as a Framework for Completeness Theorems III”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 115 (3): 241–274.

- Makkai, M., 1998, “Towards a Categorical Foundation of Mathematics”, Lecture Notes in Logic (Volume 11), Berlin: Springer, 153–190.

- Makkai, M., 1999, “On Structuralism in Mathematics”, Language, Logic and Concepts, Cambridge: MIT Press, 43–66.

- Makkai, M. & Paré, R., 1989, Accessible Categories : the Foundations of Categorical Model Theory, Contemporary Mathematics 104, Providence: AMS.

- Makkai, M. & Reyes, G., 1977, First-Order Categorical Logic, Springer Lecture Notes in Mathematics 611, New York: Springer.

- Makkei, M. & Reyes, G., 1995, “Completeness Results for Intuitionistic and Modal Logic in a Categorical Setting”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 72 (1): 25–101.

- Marquis, J.-P., 1993, “Russell's Logicism and Categorical Logicisms”, Russell and Analytic Philosophy, A. D. Irvine & G. A. Wedekind, (eds.), Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 293–324.

- Marquis, J.-P., 1995, “Category Theory and the Foundations of Mathematics: Philosophical Excavations”, Synthese, 103: 421–447.

- Marquis, J.-P., 2000, “Three Kinds of Universals in Mathematics?”, in Logical Consequence: Rival Approaches and New Studies in Exact Philosophy: Logic, Mathematics and Science, Vol. II, B. Brown & J. Woods (eds.), Oxford: Hermes, 191–212.

- Marquis, J.-P., 2006, “Categories, Sets and the Nature of Mathematical Entities”, in The Age of Alternative Logics. Assessing philosophy of logic and mathematics today, J. van Benthem, G. Heinzmann, Ph. Nabonnand, M. Rebuschi, H. Visser (eds.), Springer, 181–192.

- Marquis, J.-P., 2009, From a Geometrical Point of View: A Study in the History and Philosophy of Category Theory, Berlin: Springer.

- Marquis, J.-P. & Reyes, G., to appear, “The History of Categorical Logic: 1963–1977”, Handbook of the History of Logic, Vol. 6, D. Gabbay & J. Woods, eds., Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- McLarty, C., 1986, “Left Exact Logic”, Journal of Pure and Applied Algebra, 41 (1): 63–66.

- McLarty, C., 1990, “Uses and Abuses of the History of Topos Theory”, British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 41: 351–375.

- McLarty, C., 1991, “Axiomatizing a Category of Categories”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 56 (4): 1243–1260.

- McLarty, C., 1992, Elementary Categories, Elementary Toposes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McLarty, C., 1993, “Numbers Can be Just What They Have to”, Noûs, 27: 487–498.

- McLarty, C., 1994, “Category Theory in Real Time”, Philosophia Mathematica, 2 (1): 36–44.

- McLarty, C., 2004, “Exploring Categorical Structuralism”, Philosophia Mathematica, 12: 37–53.

- McLarty, C., 2005, “Learning from Questions on Categorical Foundations”, Philosophia Mathematica, 13 (1): 44–60.

- McLarty, C., 2006, “Emmy Noether's set-theoretic topology: from Dedekind to the rise of functors”, The Architecture of Modern * * Mathematics, J.J. Gray & J. Ferreiros, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 187–208.

- Moerdijk, I., 1984, “Heine-Borel does not imply the Fan Theorem”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 49 (2): 514–519.

- Moerdijk, I., 1995a, “A Model for Intuitionistic Non-standard Arithmetic”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 73 (1): 37–51.

- Moerdijk, I., 1998, “Sets, Topoi and Intuitionism”, Philosophia Mathematica, 6 (2): 169–177.

- Moerdijk, I. & Palmgren, E., 1997, “Minimal Models of Heyting Arithmetic”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 62 (4): 1448–1460.

- Moerdijk, I. & Palmgren, E., 2002, “Type Theories, Toposes and Constructive Set Theory: Predicative Aspects of AST”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 114 (1–3): 155–201.

- Moerdijk, I. & Reyes, G., 1991, Models for Smooth Infinitesimal Analysis, New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Pareigis, B., 1970, Categories and Functors, New York: Academic Press.

- Pedicchio, M. C. & Tholen, W., 2004, Categorical Foundations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Peirce, B., 1991, Basic Category Theory for Computer Scientists, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Pitts, A. M. & Taylor, P., 1989, “A Note of Russell's Paradox in Locally Cartesian Closed Categories”, Studia Logica, 48 (3): 377–387.

- Pitts, A. M., 1987, “Interpolation and Conceptual Completeness for Pretoposes via Category Theory”, Mathematical Logic and Theoretical Computer Science (Lecture Notes in Pure and Applied Mathematics, Volume 106), New York: Dekker, 301–327.

- Pitts, A. M., 1989, “Conceptual Completeness for First-order Intuitionistic Logic: an Application of Categorical Logic”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 41 (1): 33–81.

- Pitts, A. M., 1992, “On an Interpretation of Second-order Quantification in First-order Propositional Intuitionistic Logic”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 57 (1): 33–52.

- Pitts, A. M., 2000, “Categorical Logic”, Handbook of Logic in Computer Science, Vol.5, Oxford: Oxford Unversity Press, 39–128.

- Plotkin, B., 2000, “Algebra, Categories and Databases”, Handbook of Algebra, Vol. 2, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 79–148.

- Porter, T., 2004, “Interpreted Systems and Kripke Models for Multiagent Systems from a Categorical Perspective”, Theoretical Computer Science, 323 (1–3): 235–266.

- Reyes, G., 1991, “A Topos-theoretic Approach to Reference and Modality”, Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic, 32 (3): 359–391.

- Reyes, G. & Zawadowski, M., 1993, “Formal Systems for Modal Operators on Locales”, Studia Logica, 52 (4): 595–613.

- Reyes, G. & Zolfaghari, H., 1991, “Topos-theoretic Approaches to Modality”, Category Theory (Como 1990) (Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Volume 1488), Berlin: Springer, 359–378.

- Reyes, G. & Zolfaghari, H., 1996, “Bi-Heyting Algebras, Toposes and Modalities”, Journal of Philosophical Logic, 25 (1): 25–43.

- Reyes, G., 1974, “From Sheaves to Logic”, in Studies in Algebraic Logic, A. Daigneault, ed., Providence: AMS.

Rodabaugh, S. E. & Klement, E. P., eds., Topological and Algebraic Structures in Fuzzy Sets: A Handbook of Recent Developments in the Mathematics of Fuzzy Sets (Trends in Logic, Volume 20), Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Scedrov, A., 1984, Forcing and Classifying Topoi, Providence: AMS.

- Scott, P.J., 2000, “Some Aspects of Categories in Computer Science”, Handbook of Algebra, Vol. 2, Amsterdam: North Holland, 3–77.

- Seely, R. A. G., 1984, “Locally Cartesian Closed Categories and Type Theory”, Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Mathematical Society, 95 (1): 33–48.

- Shapiro, S., 2005, “Categories, Structures and the Frege-Hilbert Controversy: the Status of Metamathematics”, Philosophia Mathematica, 13 (1): 61–77.

- Sica, G., ed., 2006, What is Category Theory?, Firenze: Polimetrica.

- Taylor, P., 1996, “Intuitionistic sets and Ordinals”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 61: 705–744.

- Taylor, P., 1999, Practical Foundations of Mathematics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tierney, M., 1972, “Sheaf Theory and the Continuum Hypothesis”, Toposes, Algebraic Geometry and Logic, F.W. Lawvere (ed.), Springer Lecture Notes in Mathematics 274, 13–42.

- Van Oosten, J., 2002, “Realizability: a Historical Essay”, Mathematical Structures in Computer Science, 12 (3): 239–263.

- Van Oosten, J., 2008, Realizability: an Introduction to its Categorical Side (Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, Volume 152), Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Van der Hoeven, G. & Moerdijk, I., 1984a, “Sheaf Models for Choice Sequences”, Annals of Pure and Applied Logic, 27 (1): 63–107.

- Van der Hoeven, G. & Moerdijk, I., 1984b, “On Choice Sequences determined by Spreads”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, 49 (3): 908–916.

- Van der Hoeven, G. & Moerdijk, I., 1984c, “Constructing Choice Sequences for Lawless Sequences of Neighbourhood Functions”, Models and Sets (Lecture Notes in Mathematics, Volume 1103), Berlin: Springer, 207–234.

- Wood, R.J., 2004, “ Ordered Sets via Adjunctions”, Categorical Foundations, M. C. Pedicchio & W. Tholen, eds., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yanofski, N., 2003, “A Universal Approach to Self-Referential Paradoxes, Incompleteness and Fixed Points”, The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic, 9 (3): 362–386.

Lien externe

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.