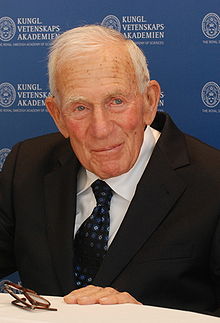

- Walter Munk

-

Walter Munk

Naissance modifier

Walter Heinrich Munk, né le 19 octobre 1917, est un océanographe américain[1]. Il est professeur de géophysique emeritus et porte le titre de Secretary of Navy/Chief of Naval Operations Oceanography Chair at Scripps Institution of Oceanography à La Jolla (Californie).

Sommaire

Enfance

Né en 1917 à Vienne (Autriche-Hongrie), Munk fut envoyé en pension dans une école préparatoire pour garçons dans l'État de New York en 1932[2],[3]. Sa famille avait choisi New York car elle envisageait que le jeune Walter fasse une carrière dans la finance dans une banque new-yorkaise liée à l'entreprise familiale. Son père, Hans Munk, et sa mère, Rega Brunner, avaient divorcé alors que Walter était encore enfant. Son grand-père maternel, Lucian Brunner (1850-1914). Son beau-père, Dr Rudolf Engelsberg, fut brièvement membre du gouvernement autrichien du Président Engelbert Dollfuss[4].

Munk travailla trois ans à la banque et étudia à l'Université Columbia. Il n'aimait pas la finance et quitta la banque pour étudier au California Institute of Technology, où il obtint sa licence en physique en 1939. Il fit un stage à l'Institut d'Océanographie de Scripps et l'année suivante, le directeur de Scripps, le distingué océanographe Harald Ulrik Sverdrup l'accepta en programme de doctorat mais lui fit savoir qu'il ne connaissait pas un seul poste d'océanographe disponible dans les dix prochaines années.

Munk termina sa maîtrise en géophysique en 1940 et le doctorat en océanographie University of California, Los Angeles, en 1947. Le Scripps Institution of Oceanography à La Jolla l'embaucha en tant qu'assistant professeur de géophysique. Il devint professeur en 1954.

En 1968, Munk devint membre du groupe JASON, un panel de scientifiques qui conseille le gouvernement américain.

Le 20 juin 1953, Munk épousa Judith Horton. Elle était active à l'Institut d'Océanographie de Scripps pendant plusieurs décennies, contribuant à son architecture, planning et à la rénovation et réutilisation de bâtiments historiques. Judith Munk est décédée le 19 mai 2006. Munk se remaria avec Mary Coakley en juin 2011.

War activities

Munk applied for American citizenship in 1939 after the Anschluss and enlisted in the ski troops of the U.S. Army as a private. This was unusual as all the other young men at Scripps joined the U.S. Naval Reserve. Munk was eventually excused from military service to undertake defense related research at Scripps. He joined several of his colleagues from Scripps at the U.S. Navy Radio and Sound Laboratory, where they developed methods related to amphibious warfare. Their methods were used successfully to predict surf conditions for Allied landings in North Africa, the Pacific theater of war, and on D-Day during the Normandy invasion[4]. Munk commented in 2009, "The Normandy landing is famous because weather conditions were very poor and you may not realize it was postponed by General Eisenhower for 24 hours because of the prevailing wave conditions. And then he did decide, in spite of the fact that conditions were not favorable, it would be better to go in than lose the surprise element, which would have been lost if they waited for the next tidal cycle two weeks."[5]

The Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics in La Jolla, IGPP/LJ

Returning to Scripps from a sabbatical at Cambridge University in England, in 1956 Munk developed plans for a La Jolla branch of the Institute of Geophysics, then a part of the University of California, Los Angeles. With the new branch of IGP, an institution of the wider University of California system, to be focused on planetary physics with an emphasis on the Earth-Moon system, IGP changed its name to the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, IGPP. IGPP at La Jolla was built between 1959-1963 with funding from the University of California, the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation, and private foundations[6],[7], The redwood building was designed by architect Lloyd Ruocco, in close consultation with Judith and Walter Munk. The IGPP buildings have become the center of the Scripps campus. Among the early faculty appointments were Carl Eckart, George Backus, Freeman Gilbert and John Miles. In 1971 an endowment of $600,000 was established by Cecil Green to support visiting scholars, now known as Green Scholars. Munk served as director of IGPP/LJ from 1963-1982.

In the late 1980s, plans for an expansion of IGPP were developed by Judith and Walter Munk, and Sharyn and John Orcutt, in consultation with a local architect, Fred Liebhardt. The Revelle Laboratory was completed in 1993. At this time the original IGPP building was renamed the Walter and Judith Munk Laboratory for Geophysics. In 1994 the Scripps branch of IGPP was renamed the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics.

Research

After World War II Munk helped to analyze the currents, diffusion, and water exchanges at Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific, where the United States was testing nuclear weapons.

Wind driven gyres

Munk pioneered research on the relationship between winds and ocean circulation, coining the now widely used term "wind-driven gyres."[8]

Rotation of the earth

Munk was the first to show rigorously why one side of the moon always faces the earth (Munk and McDonald, 1960; and later papers up to 1975), a phenomenon known as tidal locking. Lord Kelvin had also considered this question, and had fashioned a non-quantitative answer being roughly correct. The moon does not have a molten liquid core, so cannot rotate through the egg-shaped distortion caused by the Earth's gravitational pull. Rotation through this shape requires internal shearing, and only fluids are capable of such rotation with small frictional losses. Thus, the pointy end of the "egg" is gravitationally locked to always point directly towards the earth, with some small librations, or wobbles. Large objects may strike the moon from time to time, causing it to rotate about some axis, but it will quickly stop rotating. All frictional effects from such events will also cause the moon to regress further away from the earth.

In the 1950s, Munk investigated irregularities in the Earth's rotation, such as the Chandler wobble and annual and long-term changes in the length of day (rate of the Earth's rotation), to see how these were related to geophysical processes such as the changes in the atmosphere, ocean, and core, and the energy dissipated by tidal acceleration. He also investigated how western boundary currents, such as the Gulf Stream, dissipated planetary vorticity. His inviscid theory of these currents did not have a time invariant solution; no simple solution to this problem has ever been found.[citation nécessaire]

Project Mohole

In 1957, Munk and Harry Hess suggested the idea behind Project Mohole: to drill into the Mohorovicic Discontinuity and obtain a sample of the Earth's mantle. While such a project was not feasible on land, drilling in the open ocean would be more feasible, because the mantle is much closer to the sea floor. Initially led by the informal group of scientists known as the American Miscellaneous Society (AMSOC, including Hess, Maurice Ewing, and Roger Revelle)[3], the project was eventually taken over by the National Science Foundation (NSF). Initial test drillings into the sea floor led by Willard Bascom occurred off Guadalupe Island, Mexico in March and April 1961[9]. The project became mismanaged and increasingly expensive after Brown and Root won the contract to continue the effort, however, and Congress discontinued the project toward the end of 1966[10]. While Project Mohole was not successful, the idea led to projects such as NSF's Deep Sea Drilling Program[11].

Ocean swell

Starting in the late 1950s Munk returned to the study of ocean waves, and, thanks to his acquaintance with John Tukey, he pioneered the use of power spectra in describing wave behavior. This work culminated with an experiment that he led in 1963 to observe waves generated by winter storms in the Southern Hemisphere and traveling thousands of miles throughout the Pacific ocean. To trace the path and decay of waves as they propagated northward, he established stations to measure waves from islands and at sea (on R/P FLIP) along a great circle from New Zealand to Alaska. The results showed little decay of wave energy with distance traveled[12]. This work, together with the wartime work on wave forecasting, led to the science of surf forecasting, one of Munk's best-known accomplishments[5]. Munk's pioneering research into surf forecasting was acknowledged in 2007 with an award from the Groundswell Society, a surfing advocacy organization[13],[14].

Ocean tides

Partially motivated by their effects on the Earth's rotation, between 1965 and 1975 Munk turned to investigations of ocean tides. Modern methods of time-series and spectral analysis were brought to bear on tidal analysis, leading to the development of the "response method" of tidal analysis[15]. With Frank Snodgrass, Munk developed deep-ocean pressure sensors that could be used to provide tidal data far from any land[2],[16]. One highlight of this work was the discovery of the semidiurnal amphidrome midway between California and Hawaii[17].

Ocean acoustic tomography

Beginning in 1975, Munk and Carl Wunsch of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology pioneered the development of acoustic tomography of the ocean[18]. With Peter Worcester, Munk developed the use of sound propagation, particularly sound arrival patterns and travel times, to infer important information about the ocean's large-scale temperature and current. This work, together with the work of other groups[19], eventually motivated the 1991 "Heard Island Feasibility Test", to determine if man-made acoustic signals could be transmitted over antipodal distances to measure the ocean's climate. The experiment came to be called "the sound heard around the world." During six days in January 1991, acoustic signals were transmitted by sound sources lowered from the M/V Cory Chouest near Heard Island in the southern Indian Ocean. These signals traveled half-way around the globe to be received on the east and west coasts of the United States, as well as at many other stations around the world.[20] The follow-up to this experiment was the 1996-2006 Acoustic Thermometry of Ocean Climate (ATOC) project in the North Pacific Ocean[21],[22], which engendered considerable public controversy concerning the effects of man-made sounds on marine mammals[23],[24],[25].

Tides and mixing

In recent years Munk has returned to the work on the role of tides in producing mixing in the ocean[26]. In a 1966 paper "Abyssal Recipes", Munk was one of the first to quantitatively assess the rate of mixing in the abyssal ocean in maintaining oceanic stratification[27]. According to Sandström's theorem (1908), without the occurrence of mixing in the abyssal ocean, such as may be driven by internal tides, most of the ocean would become cold and stagnant, capped by a thin, warm surface layer.

Munk has also recently focused on the relation between changes in ocean temperature, sea level, and the transfer of mass between continental ice and the ocean.

Récompenses

Munk was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1956 and to the Royal Society of London in 1976. He has been a both a Guggenheim Fellow (three times) and a Fulbright Fellow. He was also named California Scientist of the Year by the California Museum of Science and Industry in 1969. Among the many other awards and honors Munk has received are the Arthur L. Day Medal, from the Geological Society of America in 1965, the Sverdrup Gold Medal of the American Meteorological Society in 1966, the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1968, the first Maurice Ewing Medal sponsored by the American Geophysical Union and the U.S. Navy in 1976, the Alexander Agassiz Medal of the National Academy of Sciences in 1977, the Captain Robert Dexter Conrad Award from the U.S. Navy in 1978, the National Medal of Science in 1985, the William Bowie Medal of the American Geophysical Union in 1989, the Vetlesen Prize in 1993, the Kyoto Prize in 1999, the first Prince Albert I Medal in 2001, and the Crafoord Prize of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 2010 “for his pioneering and fundamental contributions to our understanding of ocean circulation, tides and waves, and their role in the Earth′s dynamics”.

In 1993 Munk was the first recipient of the Walter Munk Award given "in Recognition of Distinguished Research in Oceanography Related to Sound and the Sea."[28] This award is given jointly by the Oceanography Society, the Office of Naval Research and the Office of the Oceanographer of the Navy[28].

Livres

- W. Munk and G.J.F. MacDonald, The Rotation of the Earth: A Geophysical Discussion, Cambridge University Press, 1960, revised 1975. ISBN 0-521-20778-9

- W. Munk, P. Worcester, and C. Wunsch, Ocean Acoustic Tomography, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-47095-1

- S. Flatté (ed.), R. Dashen, W. H. Munk, K. M. Watson, F. Zachariasen, Sound Transmission through a Fluctuating Ocean, Cambridge University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0521219402

Documentaires/Films

- "Waves Across the Pacific" (1963) This documentary showcases Munk's research on waves generated by Antarctic storms. The film documents Munk's collaboration as they track storm-driven waves from Antarctica across the Pacific Ocean to Alaska. The film features scenes of early digital equipment in use in field experiments with Munk's commentary on how unsure they were about using such new technology in remote locations.

- One Man's Noise: Stories of An Adventuresome Oceanographer (1994) A television program on the work and life of Walter Munk produced by the University of California. (YouTube link)

- Perspectives on Ocean Science: Global Sea Level: An Enigma (2004) A seminar on global sea level and climate change by Walter Munk. (YouTube link)

- The Sound of Climate Change (2010) Munk's Crafoord Prize Lecture

References

- Yam, P. (1995) Profile: Walter H. Munk – The Man Who Would Hear Ocean Temperatures, Scientific American 272(1), 38-40.

- Munk, Walter H., « Affairs of the Sea », dans Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, vol. 8, 1980, p. 1–17 [texte intégral, lien DOI]

- (en) Hans von Storch et Klaus Hasselmann, Seventy Years of Exploration in Oceanography: A Prolonged Weekend Discussion with Walter Munk, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, 2010 (ISBN 978-3-642-12086-2)

- Pepita Adelmann, « Introducing Walter Munk, or "The Old Man and the Sea" », dans Bridges, vol. 17, 2008-04-15 [texte intégral (page consultée le 2010-08-13)]

- Walter Munk: One Of The World's Greatest Living Oceanographers, CBS 8 (November 2, 2009). Consulté le 2010-08-20.

- Modèle:Cite article

- The Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP). Consulté le 2010-11-02.

- W. Munk, « On the wind-driven ocean circulation », dans J. Meteorology, vol. 7, 1950, p. 79–93

- Steinbeck, John : High drama of bold thrust through the ocean floor: Earth's second layer is tapped in prelude to MOHOLE, Life Magazine (April 14, 1961). Consulté le September 11, 2010.

- Sweeney, Daniel : Why Mohole was no hole, Invention and Technology Magazine - American Heritage, pp. 55–63. Consulté le August 14, 2011.

- The National Academies : Project Mohole 1958-1966. Consulté le September 5, 2010.

- F.E. Snodgrass, « Propagation of ocean swell across the Pacific », dans Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A, vol. 259, 1966, p. 431–497 [lien DOI (page consultée le 2010-07-22)]

- Fikes, Bradley : SIO’s Walter Munk Wins Crafoord Prize, North County Times blogs (January 21, 2010). Consulté le August 20, 2010.

- Casey, Shannon : Isn't He Swell?, Explorations (May 2007). Consulté le August 20, 2010.

- W. Munk, « Tidal spectroscopy and prediction », dans Phil Trans R. Soc. London, vol. A 259, 1966, p. 533–581

- (en) David Cartwright, Tides: A Scientific History, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1999 (ISBN 0-521-62145-3)

- W. Munk, « Tides off shore: transition from California coastal to deep-sea waters », dans Geophys. Fluid Dyn., vol. 1, 1970, p. 161–235 [lien DOI]

- (en) Walter Munk et Peter Worcester and Carl Wunsch, Ocean Acoustic Tomography, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995 (ISBN 0-521-47095-1)

- J.L. Spiesberger, « Basin-scale tomography: A new tool for studying weather and climate », dans J. Geophys. Res., vol. 96, 1991, p. 4869–4889

- W. Munk, « The Heard Island Papers: A contribution to global acoustics », dans Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 96, 1994, p. 2327–2329 [lien DOI (page consultée le 2010-07-22)]

- The ATOC Consortium : Ocean Climate Change: Comparison of Acoustic Tomography, Satellite Altimetry, and Modeling, Science Magazine (1998-08-28), pp. 1327–1332. Consulté le 2007-05-28.

- Dushaw, B.D. ; et al. : A decade of acoustic thermometry in the North Pacific Ocean, J. Geophys. Res. (2009-07-19).

- Stephanie Siegel : Low-frequency sonar raises whale advocates' hackles, CNN (June 30, 1999). Consulté le 2007-10-23.

- Malcolm W. Browne : Global Thermometer Imperiled by Dispute, NY Times (June 30, 1999). Consulté le 2007-10-23.

- Potter, J. R. : ATOC: Sound Policy or Enviro-Vandalism? Aspects of a Modern Media-Fueled Policy Issue, The Journal of Environment & Development, pp. 47–62. Consulté le 2009-11-20.

- Munk, W., and Wunsch, C., « Abyssal recipes II: Energetics of tidal and wind mixing », dans Deep-Sea Res., vol. 45, 1998, p. 1977–2010 [lien DOI]

- Munk, W., « Abyssal recipes », dans Deep-Sea Res., vol. 13, 1966, p. 707–730

- The Walter Munk Award, Oceanography Society. Consulté le 26 July 2010

Liens externes

- Scripps Institution of Oceanography

- UCSD Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP)

- Biography UCSD

- Biography Columbia U.

- Oral History interview transcript with Walter Munk 30 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

- Kyoto Prize

- The Heard Island Feasibility Test

- Portail du monde maritime

- Portail de la Californie

- Portail des sciences de la Terre et de l’Univers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.